After ten days of travel, my older daughter returned home from a school-sponsored trip to India and told me of her visit to Nirmal Hriday, the home founded by Mother Theresa for the sick and dying. I knew this is the closest my daughter has come to touching death. She recounted for me her arrival at Nirmal Hriday, where a staff member handed her a white plastic block with terse instructions to massage the skin and bones of the bed-bound patients to prevent sores. I imagined her standing with block in hand, silent and unsure.

The staff asked her to speak to the patients as she touched them, but she found her words to be a cold, impractical comfort. First, there was the language barrier. Second, the fact that she was 19 and unfamiliar with suffering. So without speaking, she tended to their bodies and held hands with the dying. She sang them soft melodies instead.

As she shared the details with me, I anticipated her patients’ questions. Was this appropriate? If I were dying alone in a bed on the far side of the world, would I want the strange song and tender touch of a young foreigner to usher me into the thin place between earth and heaven?

The name Nirmal Hriday translates to “pure heart” in Hindi. Was this home named for the caregivers or the patients, I wondered. Mother Theresa once said of her work there, “A beautiful death is for people who lived like animals to die like angels—loved and wanted." Was this the beautiful death they wanted?

Months later, my younger daughter walked through the kitchen as I scrubbed dishes, and over the soft whish of water and soap, she told me she’d completed her school assignment of studying the Rohingya, a persecuted people group. In her report, she followed their migration as they sought shelter and safety in other countries and looked for a glimpse of shared humanity. She slammed the pantry door shut after rummaging for a snack and announced over the running water, “They’re called the most friendless people in the world. It’s tragic.”

If I were dying alone, would I want the strange song and tender touch of a young foreigner to usher me into the thin place between earth and heaven?

As my daughter walked out of the kitchen, a lyric to a song we sang at church rose from my memory. “I am a friend of God,” it went, and I wondered if the friendless Rohingya felt a connection to God as they wandered. Do they sing songs of deliverance in their native tongue?

Over time I’ve collected my thoughts on suffering in a hidden, inner place. Persecuted people groups take up residence there, and I try to empathize with the ones hated for who they are and how they struggle. There, in my heart, the Rohingya mingle with the Pure Hearts of India.

Along with stories about the Rohingya and those dying in India, I’ve gathered accounts of immigrant families seeking safety. A few years ago a friend from Nebraska sponsored a Yazidi refugee family who arrived on asylum from Iraq. They were unable to communicate with her for months, except through translators and physical gestures. After they settled in, the family showed their thanks with an invitation to dinner, and my friend messaged me to say, “What will we talk about? We don’t understand each other’s language!” They feasted on authentic Iraqi food from comfortably cross-legged positions on the floor of the family’s new apartment.

“They’re called the most friendless people in the world.”

Over time, the family began to absorb American culture while attending school, learning English, and attempting to assimilate. They even gave their newborn daughter the very American name of my friend, who wondered why they chose that. I believe it’s because they understood her “language.” Her care for them spoke quietly of God, friendship, acceptance, and belonging.

When I close my eyes and travel to this inner place where the persecuted, the poor, and the friendless gather, I see Christ at the center of all of these stories of suffering. He, too, embodied an otherness. He, too, set a table. He, too, wandered and endured great pain. Christ communicated through a universal language that people across all cultures and all time periods understand if we choose to listen. He modeled love so that we may learn to speak redemption into one another’s stories.

Paul writes in 1 Corinthians, “If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but do not have love, I have become a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal” (1 Corinthians 13:1). I am guilty of this noisy, loveless clanging, but as a follower of Christ, I must remind myself: Love is our native tongue. It is our first language.

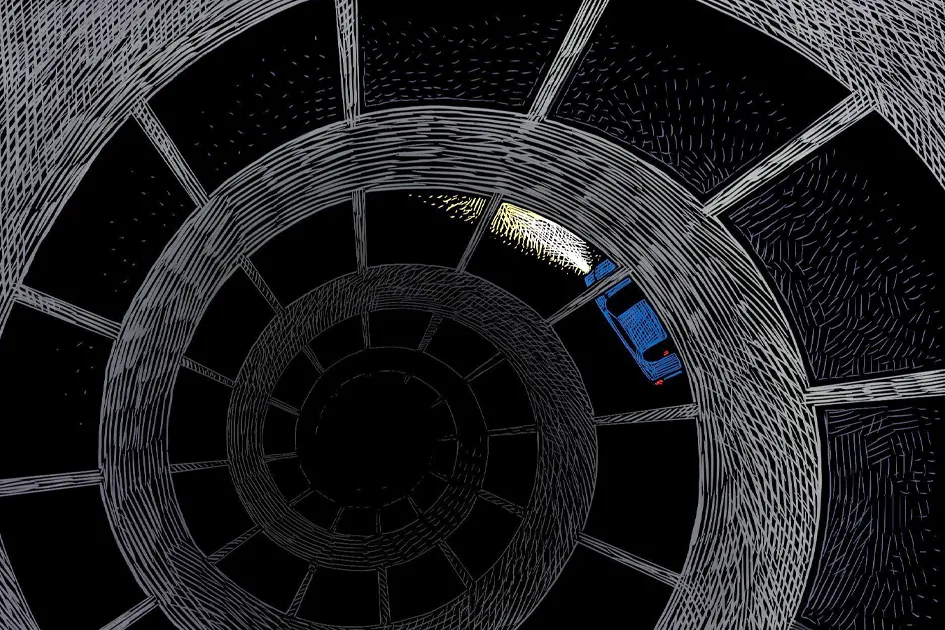

Illustration by Adam Cruft